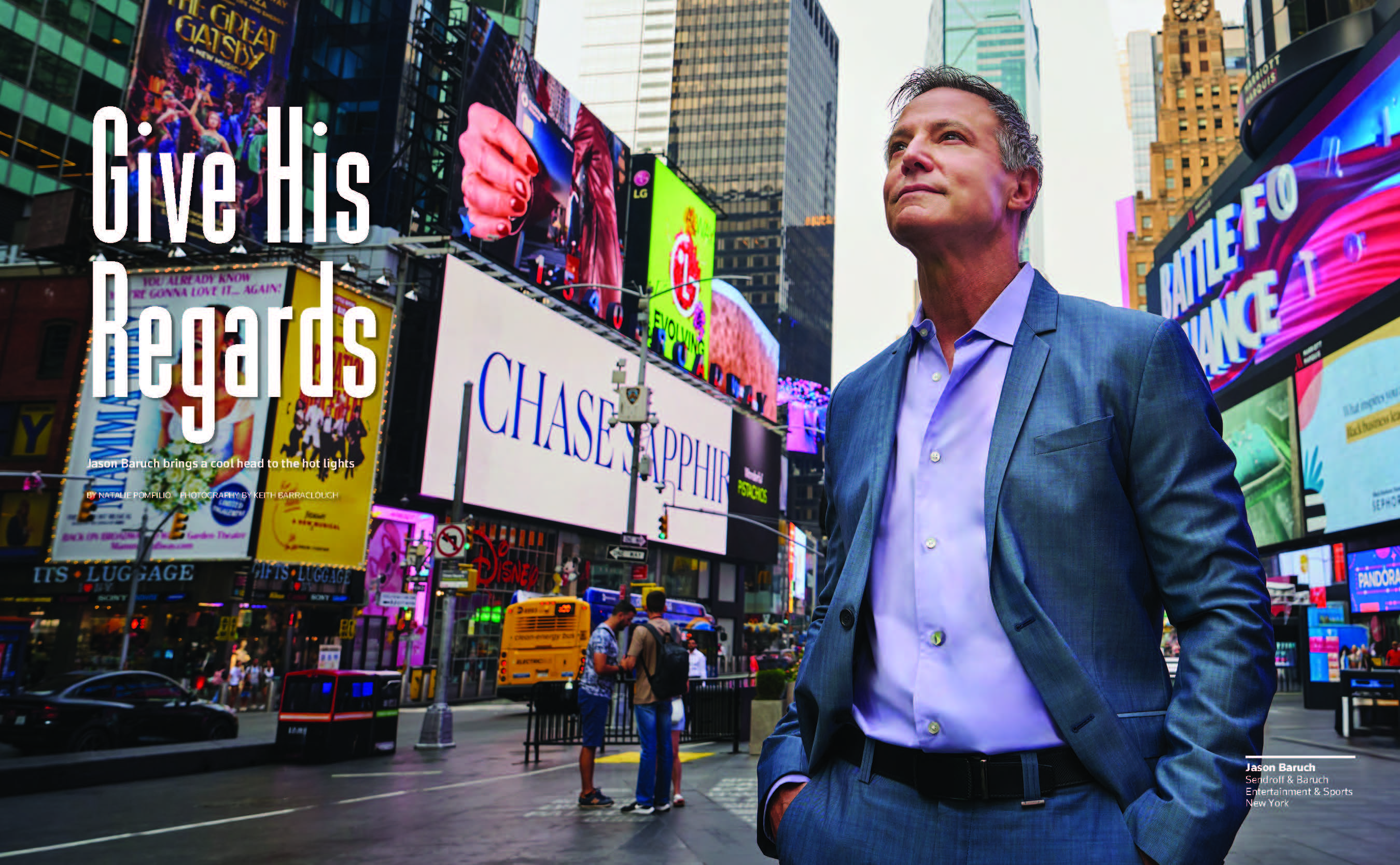

Jason Baruch Profiled for New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine

Jason Baruch brings a cool head to the hot lights

By Natalie Pompilio on October 28, 2025

Published in 2025 New York Metro Super Lawyers magazine

Broadway is a fickle business. Years of work and millions of dollars can produce a must-see musical or an overnight flop. You never know.

But sometimes you do.

“There are moments when you are seeing or hearing something for the first time,” says entertainment attorney Jason Baruch, “sitting on the edge of your plastic seat in this small, uncomfortable rehearsal room, and you feel, ‘This is going to be something.’ It’s thrilling.”

Baruch felt that thrill when he first heard a jukebox musical about a decades-old doo-wop group (Jersey Boys), a coming-of-age rock show inspired by an 1891 German play (Spring Awakening), and a hip-hop reinvention of one of the lesser-known founding fathers (Hamilton).

Yes, Baruch admits, there have also been times when he’s left a reading or a rehearsal thinking, “There’s three hours of my life I’m not going to get back.” But even then, he says, he appreciates the energy and passion creators put into their projects. “To be successful in this job,” he says, “you have to love what you do.”

The eponymous firm Baruch founded with partner Mark Sendroff in 2007 represents dramatists, actors, directors—anyone connected with the stagecraft of the Great White Way. Among his Broadway shows this past season, Baruch was production counsel for Buena Vista Social Club, which was nominated for 10 Tony Awards and won five, and Othello, “which broke all box office records,” he says.

His theatrical pedigree extends to family. His wife, Maree Johnson, is a Broadway performer whose credits include Phantom of the Opera and Masquerade, while his father, Steven, is a co-founder and president of 54 Below, a nonprofit cabaret and restaurant, and a producer of dozens of Broadway hits, including Smokey Joe’s Café, Angels in America, Hairspray and The Producers.

“Jason is more than just a legal eagle in the arts; he understands the theater from a multiplicity of perspectives,” says Doug Wright, whose play I Am My Own Wife earned him a Pulitzer Prize for Drama and a Tony Award for Best Play in 2004. “He gets all the exhilaration, all the stress, and all the madness that exists in our field.”

At the same time, he doesn’t let all that get in the way of his work. “Nothing throws him,” says Sendroff. “I’ve rarely heard him raise his voice. He’s very good at problem-solving without looking like he’s trying. It seems effortless, and he explains [his position] in a way that’s very convincing.”

Producer Orin Wolf, whose credits include The Band’s Visit, Once, and Buena Vista Social Club, says Baruch appreciates artists and their artistry and is eager to find ways to help them share their work. “There are a lot of lawyers in our business who can be somewhat obstructionist. He is someone who is always interested in making a deal, who understands that our business operates within a very small group of people and it’s always about relationships,” Wolf says. “There is risk everywhere in the theater world, and you need a lawyer who can appreciate and embrace that and understand that it’s true for both sides.”

Baruch provides more than sound legal advice, Wolf adds. “I always feel like he’s coming to the table as a collaborator, as someone who is in it with me,” he says.

Baruch grew up in Westchester with two siblings and film-buff parents. When other kids were reading the funny pages, he was studying the weekly box office grosses in Variety magazine.

“I don’t know why, but I became obsessed with the numbers. I would memorize every weekly box office take of every movie that was playing at the time,” Baruch says. “The list was on the back page of Variety every week, and that was the first page I would go to.”

Back then his father Steven was in the real estate business. But he and wife Eda always appreciated a good stage show and wanted to share that love with their children. Baruch was in primary school when they took him to his first musical, The Magic Show, starring Doug Henning.

“I think they were looking for some way to introduce me to musicals without freaking me out, and they knew I loved magic,” Baruch says. “It worked. I was very much smitten by the business, and by theater—and musical theater in particular.”

Even so, his path to entertainment law included a few off-roads. After studying philosophy at Yale, he went west to check out the movie business, taking a job in the mailroom of an LA talent agency. But the firm closed so Baruch rescinded his deferment to New York University School of Law. There, while working summers for two Century City entertainment firms, he tried to take its single entertainment law class but couldn’t get in. The two professors of that course later became his legal partners. “I used to tease them about not accepting me,” Baruch says.

J.D. in hand, he went west again, this time clerking in the Santa Monica office for Judge Ruggero J. Aldisert of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit. He took the Bar in New York and California, passing both. “So I continued to hedge my bets even after law school,” he says.

A job at a large Manhattan litigation firm representing reinsurance companies wasn’t a good fit. “It was so far removed from anything that felt real to me that I decided litigation wasn’t what I wanted to be doing,” he says.

Needing a reset, he opted to move overseas to study international trade law at the University of Hong Kong law school. He calls it “a bit of a digression,” but it gave him room to recalibrate and refocus. After earning his master’s in 1997, he began looking for jobs in the States. He reached out to a boutique law firm in New York, Franklin Weinrib Rudell & Vassallo, because his accountant had been college roommates with one of the partners.

The firm wasn’t hiring but the lawyers said they’d be happy to meet Baruch if he happened to be in the city. Within days, Baruch made sure he happened to be in the city. There were still no openings but the meeting with the head of the theater division went well. Two months later, he called the firm again with a casual, “Hey, I’m back in New York …” This time, he met with five of the firm’s partners. Again, it went well. Again, no openings.

Third time was the charm. One of the managing partners invited him to the Friars Club for lunch, and an offer was extended. The timing was propitious. Not a lot of people were “rustling to get into theater,” Baruch says. “I made myself very available to the head of the theater department … and assumed a lot of responsibility and enjoyed a lot of independence quickly.”

Within three years he made partner. Seven years after that, he and Sendroff hung their shingle.

“When I was in litigation, it felt like people were just out to one-up each other and win. I didn’t understand how people could do it. It was such a brutal, brutal environment,” Baruch says.

In his practice area, he says, “There’s no added value to being a jerk. … We’re not trying to beat each other up.”

Persistence is key—as Baruch demonstrated when he was seeking the job in the first place. He notes there’s a difference between “quiet persistence” and antagonism. “Getting what you want, for yourself, or for your client, without looking like you’re trying that hard—or alienating folk in the process—is not a skill everyone in the business possesses,” he says.

Natalie Gershtein met Baruch 10 years ago when she was artistic director at the nonprofit Pipeline Theatre Company, where Baruch is a board member. “He really wants to make an impact,” she says.

Soon after she joined Pipeline, Gershtein recalls, the company produced a show with “a bit of a name, someone who was on Broadway, and all of a sudden, everybody and their mother was coming to me asking for more: ‘We want more money. We want more rights. We want more this, that and the other.’ I was so overwhelmed. I was so emotional about it.”

Baruch offered to help. “I will never forget his calm, cool, collected responses to everyone,” Gershtein says. “He feels passionately about the theater but he’s still a professional, so calm, so kind. People would ask for things that we could never offer and he was saying, very politely, ‘No, we can’t offer that.’”

Jason Aylesworth, a partner at Sendroff & Baruch, calls Baruch a champion of the arts. “He is very open-minded to a lot of different works,” Aylesworth says. “It could be Broadway. It could be something off-Broadway. He’s very knowledgeable about theater, but also film, television and music. That’s really important to the people he represents. They’re taking a lot of risks, putting their souls out there for audiences to consume, and the best thing [lawyers] can do is guide them properly and not let them be taken advantage of.”

Wright recalls that when he met Baruch, “I was so enthusiastic about one of my Broadway musicals that I told him I wanted to invest some of my own money in it.”

Baruch quickly put the kibosh on the idea. “‘Don’t you dare,’ he told me, ‘no matter how good you think it may be. It’s a fickle field. I’ll never let you do that,’” Wright remembers. “And thank goodness. If I had, I’d have lost my shirt.”

Baruch has impressed his father, too. “I talk to people all the time who know him or know of him,” says Steven Baruch.” It’s a universal lovefest.”

Baruch isn’t interested in becoming a producer himself. “I like being involved in dozens of projects at a time,” he says. “The ones that don’t make it, you know, are heartbreaking, but they’re a little less heartbreaking because I’ve seen so many that do break through and succeed. … The goal is to create theater and make things happen. We’re all trying to get to yes.”

The Sendroff & Baruch office is literally on Broadway in Times Square. Just negotiating the crowds of costumed characters, harried locals, gawking tourists and squawking street vendors to reach the front doors involves an air of the dramatic. “Sensory overload in the extreme,” Baruch says.

“All the time.”

From his office window, he can see at least a half dozen Broadway houses. And during his time at the firm, Baruch has seen Batman square off against the Incredible Hulk in front of the TKTS booth; taken in the Naked Cowboy and the Naked Grandma; and photobombed countless family vacation photos—accidentally or on purpose.

“Being in the thick of it reminds me daily why I am in this business,” he says. “I think clients take comfort in the fact that we are physically here, in the heart of the beast.”